Tom poured himself a cup of strong black coffee into a mug with the oversized handle for his thick fingers. He slipped his feet into flip flops, opened the sliding door of the deck, and took his first deep breath of morning air. At his cabin in northern Minnesota, the air was crisp and clean. He was located in a bend where the river widened out and the current slowed to a crawl. His girls were already leaping off the swimming dock into the water, then pulling themselves out on the stepladder, long hair streaming over their brown backs. Dodger, his six year old yellow lab, barked at them from the shore. The dog was afraid of the water, ever since he had been a puppy and had fallen off the boat.

Work flashed through Tom’s mind for a split second, an all-hands meeting to discuss the regional sales crisis in the Southwest, but work disappeared with the sound of a loon call out near Lawton’s Bay. “Girls, where’d your mother go?” he called out. But they were gone. Perhaps under the water, or hiding from him under the floating dock, giggling. He looked along the shoreline for his wife, but she wasn’t there. He would have felt completely abandoned, if it weren’t for Dodger, padding slowly along the shoreline, sniffing at the sand and river weeds for dead things.

“Dodger, where’d they all go?” The dog lifted his silver muzzle and turned to him, brown eyes returning the question.

The undisturbed slow curl of the river came around the bend and disappeared into the channel. He took another sip of coffee and pulled up a chair along the bank. He slipped off his flip flops and dug his toes into the sand. He scratched his thickly stubbled jaw and squinted to the far shore. The Emmersons waved as they loaded up their cruiser and turned on the motor. Low rumbled of their inboard, a small puff of blue smoke that would smell like oil. He waved back.

Tom was in his mid-forties, thick dark hair with a slight wave to it, graying around the sideburns. His forearms were thick but he rarely exercised or did manual labor, besides landscaping his yard back in Lakeville. Must have been genetics, he surmised, thanking his father. He wore long kaki colored shorts with large pockets that snapped closed, and an old green tee shirt, the print on the front peeling away, little holes in the short sleeves and frayed at the bottom.

Where did those girls go, he wondered, but knew it was unlikely that two girls would drown in the same moment. Just playing one of those tricks kids always like to play on adults. Kristen and Ashley, sixteen and thirteen. The older with long auburn hair, the younger as blond as her mother, curly hair bobbed short, a nose always sunburned and speckled with freckles.

His coffee had grown lukewarm. He couldn’t stand coffee any other temperature but scalding. He set the mug down in the sand and cross his legs, stretched in the warmth of the sun. Behind him his cabin sprawled, multiple levels climbing from the river-view up into the cover of the woods. He’d inherited the entire island, but this cabin was of his own making. Through the several paths worn by raccoons and the odd black bear, they could make their way to the original cottage on the other side of the island, a small but picturesque structure of mortared stones nestled on the highest point of the island. It’s rotting cedar shingled roof was smothered by towering pines. Brambles and wildberry pressed in upon it’s walls. This was just the way Tom and his wife Eileen wanted to keep it. They’d converted it into her yoga studio, where she could stretch her matt out upon the wide plank floorboards. A leaded window looked through a break in the trees to the channel.

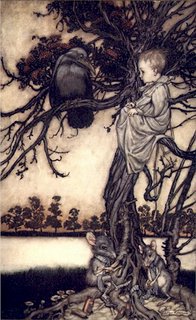

This was the original cabin of his Uncle Will. Uncle Will had been one of those tireless workers, constantly shoveling and pruning and wheelbarrowing down in the gardens and fountains that stretched down to the water. He brought back from the city by boat the stone statues of monks and Greek maidens, fountains and benches, hummingbird feeders and bags of tulip bulbs. Now the garden ran rampant. Tadpoles hatched in the fountain, overrun with algae. It was a ghost garden from which his uncle watched him, stretched out idly on the beach, with disdain.

Fuck him, Tom cursed under his breath. His Uncle Will had always frightened him as a child, glowering at the kids running through his gardens. And there was that tool shed out back, filled with frightening things like pickled rattlesnakes and skeletons of raccoons, the plaster prints of bear claws, and the rusted blades of machetes and axes and saws. It stunk in there of oil and gasoline and sweat. It was Uncle Will’s bloody chamber, he supposed, where he would hide away from his wife, from the rest of the family, sitting on that worn wooden stool by the workbench, his back turned to the world behind him.

“Daddy, Kirsten bloodied her toe!” Ashley said, clambering out of the trees. There they were, Kirsten hobbling behind her. “It’s nothing Dad, I just stubbed it on a root,” Kirsten replied.

“Girls, haven’t I told you not to run through the woods in just your swimsuits? You need to be wearing shoes for that kind of thing.”

They had probably been up at Will’s shed again, he thought to himself. Why are girls always drawn to Pandora’s box, he wondered. Sometimes late at night, when he couldn’t sleep and found himself walking the trails through the woods at night, he would come around the crest of the hill and see, coming from under the gap at the bottom of the shed door, a pale light glowing, as though from a lantern. He’d considered tearing down the shed, but backed down under the loud objections from his wife and girls.

He heard another splash. The girls were gone again. He started up towards the woods and the path that would lead towards the cottage, where he hoped to find Eileen. He whistled, then heard the familiar jingle of Dodger's tags as he padded behind him.