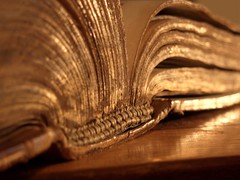

He left his apartment with a novel tucked under his arm. It was something he had wanted to get his hands on for quite some time, with leather bindings and guilt lettering along the spine; something from the 19th century, something modern but not too, but besides this, he knew hardly anything about it. He borrowed without asking from his mother’s collection.

He carried a crumpled pack of generic cigarettes in the breast pocket of his red flannel. Cherokee work boots loosely laced. Jeans with a little brake grease smeared on the knee. On the way down the steps he ran into Bridget carrying in a bag of groceries and held open the door for her. She was cute; olive skin, one dimple in her left cheek, white white teeth.

The brisk air smelled of fall, like gutted pumpkins and wet leaves. He walked a block and a half to the bus stop and picked up the 4 uptown, his final destination being a little park nestled between a row of restaurants at where he would never eat, and a trendy fitness club with valet parking.

Somebody was sitting at his favorite bench. He leaned against a tree trunk twenty yards away and stared the guy down until he got up and left. The bench overlooked a small pond ringed with cat-tails, and a playground where a young mother talked on a cell phone while two children scrambled around on the equipment.

The novel’s spine made a slight cracking sound as he opened the covers, releasing a smell of stale cigar smoke and yellowed paper. He read the first sentence, only something didn’t seem right. The words were not that of a 19th century author. There were no butlers or spinsters, no expositions of societal norms, no ladies dying of consumption. But the words spoke to him. Litterally.

Edward, you have to start doing something with your life. See that woman over there, the one on the bench watching her kids? She’s waiting, just like you. Only she’s been waiting for years, and she’s not even sure she wants kids yet, but there’s her four year old with a runny nose pushing the other kid around.

He skipped ahead: Edward, you shouldn’t skip ahead like that. You’ll miss some important information up front, some foreshadowing which might lead to misunderstanding. . .

His heart raced. He started flipping through pages:

. . . Your wife is in a coma. The doctors want to know if you’ll let her go. There are a lot of people waiting for organs right now. . .

Further ahead: Jimmy fell off his bike today and chipped a tooth. You’re going into the doctor to get tested for prostate cancer. Make sure your will is up to date.

Edward finds his place again at the beginning of the book and reads more carefully: Where did this book come from? It wasn’t really your mother’s to have. She stole it from her uncle’s library shortly after his death, during those hours when a family meets under solemn pretext, but secretly their adrenaline is pumping and their eyes scanning the room for value. “What’s mine? What her’s? No, I don’t want it, but I don’t want HER to have it, either. She always got more than me when we were kids, anyway. I should get more.”

It was during those hours of ugliness, when the pettiness of humanity reeks the most, that it turned physical. Your mother and your aunt got into a tussle, trying to reach this book tucked away on the top shelf. Your great uncle had never allowed them to play with it; everything else in the library was fair game, but never, ever, touch this book, he had warned them. Now your mother came out on top, with the leather volume clutched deftly in one arthritic claw, and tucked under her arm for good measure. A running back could have taken lessons from her on how to protect the ball, and she protected hers. All the way back home to Minneapolis.

The ownership of such a valuable book would normally lead one to display it on the optimal shelf, under just the right lighting, with only the most classic of books to nestle on either side of it. Not so with your mother. Maybe she didn’t understand the book. Maybe she feared it. She only ended up repeating the cycle, by tucking it away on the top shelf and forbidding you from ever touching it. But you didn’t wait for her estate to be divided up before getting your hands on it. You couldn’t wait, and you shouldn’t. You’ve been waiting too long for the story of your life to get interesting. Want to learn how your mother’s going to pass on, and when? Turn to page 57…

Saturday, February 24, 2007

Saturday, February 17, 2007

Plant Life

He stands in the floor to ceiling window of his condo on the thirty-second floor, looking out. He is overcome with vertigo, but it’s not the height. It’s not the city sprawled below like a safety net. It’s something to do with being alone. Or is it not being in love? Or is it the sudden realization of how he can’t seem to grow up?

To calm himself down, he makes a cup of hot chocolate. He feels at one and the same time like a mother stirring the cup with a spoon, and a little boy licking the chocolate froth off his lips. He returns to the window. A light snow transforms the world of downtown, a kind of fantasy land of glowing lights. All sounds seem to suspend in the air with the flakes and hover, like a trapeze artist caught in the moment after lunging from one rung and reaching out for the other.

He took a sleeping pill about forty-five minutes ago. He should have been down long ago. In his head he hears his own voice saying “time for bed,” like a father and the retort “but I don’t want to,” like a child. He turns his back on the window and looks towards the long path to the bedroom, and that sense of vertigo returns. He tries to make out what those shadows are across the room, tries to hear what the plants are saying to one another. One of the plants reaches around from the corner of the couch as though it plans to touch him with its palms when he passes. Another cringes in a corner, leaves pressed flat against the wall as though petrified of him. But after all, he is seeing the plants come alive. Maybe it should be afraid. Very afraid.

To calm himself down, he makes a cup of hot chocolate. He feels at one and the same time like a mother stirring the cup with a spoon, and a little boy licking the chocolate froth off his lips. He returns to the window. A light snow transforms the world of downtown, a kind of fantasy land of glowing lights. All sounds seem to suspend in the air with the flakes and hover, like a trapeze artist caught in the moment after lunging from one rung and reaching out for the other.

He took a sleeping pill about forty-five minutes ago. He should have been down long ago. In his head he hears his own voice saying “time for bed,” like a father and the retort “but I don’t want to,” like a child. He turns his back on the window and looks towards the long path to the bedroom, and that sense of vertigo returns. He tries to make out what those shadows are across the room, tries to hear what the plants are saying to one another. One of the plants reaches around from the corner of the couch as though it plans to touch him with its palms when he passes. Another cringes in a corner, leaves pressed flat against the wall as though petrified of him. But after all, he is seeing the plants come alive. Maybe it should be afraid. Very afraid.

Thursday, February 01, 2007

Rainy Florida Christmas

I sit here in Florida listening to the dull rain drip outside the window. The bug screens are beaded with water. Water drips from the overhanging tree limbs. I lay on the cot in the guestroom, stretched out to my full length so that my feet dangle over the foot of the bed. I’m sleepy, listening to the rain, smelling turkey cooking in the kitchen and my mom bustling about, opening and closing cupboards and drawers. My step dad sleeps somewhere in the reading room or the on the living room sofa, short shallow breaths like a dying fish. I try reading but I keep falling asleep. Not all the way out, but that oppressive weight on my eyes, the slightest sounds causing a terrible clamor in my head, like beads of water striking a cymbal.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)