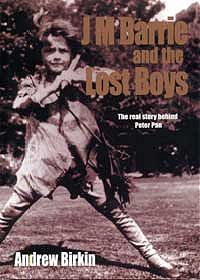

Today I finished reading the biography “JM Barrie and the Lost Boys,” by Andrew Birkin. I think I’ve been reading it for about a year. It’s been an important and comforting book for me, one which I almost didn’t want to finish, and now that I have, perhaps can attributed to my melancholy mood all day.

Today I finished reading the biography “JM Barrie and the Lost Boys,” by Andrew Birkin. I think I’ve been reading it for about a year. It’s been an important and comforting book for me, one which I almost didn’t want to finish, and now that I have, perhaps can attributed to my melancholy mood all day.But what has it meant? Why have I connected with it?

Number one, I loved reading Peter Pan, and am in awe of its endurance as a story, its tradition, and the effect it has had on children over the years. Its theme is a powerful one in my life. I too feel like a child that either won’t grow up, or can’t grow up. I seek throughout my ordinary existence ways in which to escape to a magical world like Neverland. So naturally I was entranced with the man that created all of this.

I find in Barrie a similar soul, a man subject to dark moods but whose life is so quickly brightened in the presence of a child. Watching them play; “They’re so innocent, it almost hurts” (p253). There is a magic within a child’s mind, which we are much the poorer for having lost in adulthood. It is my struggle in life to regain a little of that spark. We need not grow up, if we don’t want to. But we are also sacrificing so very much if we choose to remain a child. Marriage, children of our own, and family are all lost. I tried marriage. So did Barrie. Neither of us had much success at it.

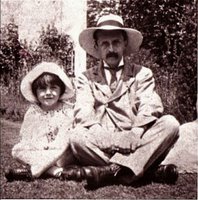

Although I’m drawing many parallels between Barrie and me, I don’t mean to say I enjoyed Birkin’s book because of these perceived parallels. I know I am no Barrie. I think I enjoyed it most because I felt like one of Barrie’s lost boys, and when I opened the book I was one of the lucky children that gathered around him and Porthos in Kensington Garden. It was less the spell of Peter Pan than that of “Uncle Jim”, cast decades later on a man who still feels like, and wants to remain, the child.

Although I’m drawing many parallels between Barrie and me, I don’t mean to say I enjoyed Birkin’s book because of these perceived parallels. I know I am no Barrie. I think I enjoyed it most because I felt like one of Barrie’s lost boys, and when I opened the book I was one of the lucky children that gathered around him and Porthos in Kensington Garden. It was less the spell of Peter Pan than that of “Uncle Jim”, cast decades later on a man who still feels like, and wants to remain, the child.So many dog-eared pages, I can jot down only a sampling of them here:

On the nature of children: “Unlike Ingley, Carroll and Wordsworth, Barrie rarely perceived children as trailing clouds of glory; he saw them as ‘gay and innocent and heartless’ creatures, inspired as much by the devil as by God. He exulted in their contradictions: their wayward appetites, their lack of morals, their conceit, their ingratitude, their cruelty, juxtaposed with gaiety, warmth, tenderness, and the sudden floods of emotion that come without warning and are as soon forgotten,” (p19).

On the actor Gerald du Maurier’s creation of Captain Hook, “Gerald was Hook; he was no dummy dressed from Simmons’ in a Clarkson wig, ranting and roaring about the stage, a grotesque figure whom the modern child finds a little comic. He was a tragic and rather ghastly creation who knew no peace, and whose soul was in torment; a dark shadow; a sinister dream; a bogey of fear who lives perpetually in the grey recesses of every small boy’s mind. All boys had their Hooks, as Barrie knew; he was the phantom who came by night and stole his way into their murky dream….And, because he had imagination and a spark of genius, Gerald made him alive,” (p110).

Two pictures of Barrie will remain with me; one, the melancholy older man who has felt “his boys” slip away from him in death or adulthood, the “Hermit of Adelphi, roosting high in his eyrie above the Thames” (p298). The other; of the magician of Kensington Gardens, creating along with five boys an inspired adventure, a fairytale bursting so suddenly into the world, like a cannon shot from the Jolly Roger.

No comments:

Post a Comment